Bitcoin

|

| Bitcoin |

Bitcoins are created as a reward for mining. They can be exchanged for other currencies, products, and services. As of February 2015, over 100,000 merchants and vendors accepted bitcoin as payment.Bitcoin can also be held as an investment. According to research produced by Cambridge University in 2017, there are 2.9 to 5.8 million unique users using a cryptocurrency wallet, most of them using bitcoin.

Terminology

The word bitcoin first occurred and was defined in the white paper that was published on 31 October 2008. It is a compound of the words bit and coin. The white paper frequently uses the shorter coin.

There is no uniform convention for bitcoin capitalization. Some sources use Bitcoin, capitalized, to refer to the technology and network and bitcoin, lowercase, to refer to the unit of account. The Wall Street Journal, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and the Oxford English Dictionary advocate use of lowercase bitcoin in all cases, a convention which this article follows.

Units

The unit of account of the bitcoin system is bitcoin. As of 2014, tickers used to represent bitcoin are BTC and XBT. Its Unicode character is ₿.[ Small amounts of bitcoin used as alternative units are millibitcoin (mBTC)[1] and satoshi. Named in homage to bitcoin's creator, a satoshi is the smallest amount within bitcoin representing 0.00000001 bitcoin, one hundred millionth of a bitcoin. A millibitcoin equals to 0.001 bitcoin, one thousandth of a bitcoin.

Design

Blockchain

The blockchain is a public ledger that records bitcoin transactions. A novel solution accomplishes this without any trusted central authority: the maintenance of the blockchain is performed by a network of communicating nodesrunning bitcoin software. Transactions of the form payer X sends Y bitcoins to payee Z are broadcast to this network using readily available software applications. Network nodes can validate transactions, add them to their copy of the ledger, and then broadcast these ledger additions to other nodes. The blockchain is a distributed database – to achieve independent verification of the chain of ownership of any and every bitcoin amount, each network node stores its own copy of the blockchain. Approximately six times per hour, a new group of accepted transactions, a block, is created, added to the blockchain, and quickly published to all nodes. This allows bitcoin software to determine when a particular bitcoin amount has been spent, which is necessary in order to prevent double-spending in an environment without central oversight. Whereas a conventional ledger records the transfers of actual bills or promissory notes that exist apart from it, the blockchain is the only place that bitcoins can be said to exist in the form of unspent outputs of transactions.

Transactions

Transactions are defined using a Forth-like scripting language. Transactions consist of one or more inputs and one or more outputs. When a user sends bitcoins, the user designates each address and the amount of bitcoin being sent to that address in an output. To prevent double spending, each input must refer to a previous unspent output in the blockchain. The use of multiple inputs corresponds to the use of multiple coins in a cash transaction. Since transactions can have multiple outputs, users can send bitcoins to multiple recipients in one transaction. As in a cash transaction, the sum of inputs (coins used to pay) can exceed the intended sum of payments. In such a case, an additional output is used, returning the change back to the payer. Any input satoshis not accounted for in the transaction outputs become the transaction fee.

Transaction fees

Paying a transaction fee is optional. Miners can choose which transactions to process and prioritize those that pay higher fees. Fees are based on the storage size of the transaction generated, which in turn is dependent on the number of inputs used to create the transaction. Furthermore, priority is given to older unspent inputs.

Ownership

In the blockchain, bitcoins are registered to bitcoin addresses. To be able to spend the bitcoins, the owner must know the corresponding private key and digitally sign the transaction. The network verifies the signature using the public key.

If the private key is lost, the bitcoin network will not recognize any other evidence of ownership; the coins are then unusable, and effectively lost. For example, in 2013 one user claimed to have lost 7,500 bitcoins, worth $7.5 million at the time, when he accidentally discarded a hard drive containing his private key. A backup of his key(s) might have prevented this.

Mining

Mining is a record-keeping service done through the use of computer processing power. Miners keep the blockchain consistent, complete, and unalterable by repeatedly verifying and collecting newly broadcast transactions into a new group of transactions called a block. Each block contains a cryptographic hash of the previous block, using the SHA-256 hashing algorithm, which links it to the previous block, thus giving the blockchain its name.

In order to be accepted by the rest of the network, a new block must contain a so-called proof-of-work. The proof-of-work requires miners to find a number called a nonce, such that when the block content is hashed along with the nonce, the result is numerically smaller than the network's difficulty target. This proof is easy for any node in the network to verify, but extremely time-consuming to generate, as for a secure cryptographic hash, miners must try many different nonce values (usually the sequence of tested values is 0, 1, 2, 3, ...) before meeting the difficulty target.

Every 2016 blocks (approximately 14 days at roughly 10 min per block), the difficulty target is adjusted based on the network's recent performance, with the aim of keeping the average time between new blocks at ten minutes. In this way the system automatically adapts to the total amount of mining power on the network.

Between 1 March 2014 and 1 March 2015, the average number of nonces miners had to try before creating a new block increased from 16.4 quintillion to 200.5 quintillion.

The proof-of-work system, alongside the chaining of blocks, makes modifications of the blockchain extremely hard, as an attacker must modify all subsequent blocks in order for the modifications of one block to be accepted. As new blocks are mined all the time, the difficulty of modifying a block increases as time passes and the number of subsequent blocks (also called confirmations of the given block) increases.

Supply

The successful miner finding the new block is rewarded with newly created bitcoins and transaction fees. As of 9 July 2016, the reward amounted to 12.5 newly created bitcoins per block added to the blockchain. To claim the reward, a special transaction called a coinbase is included with the processed payments. All bitcoins in existence have been created in such coinbase transactions. The bitcoin protocol specifies that the reward for adding a block will be halved every 210,000 blocks (approximately every four years). Eventually, the reward will decrease to zero, and the limit of 21 million bitcoins will be reached c. 2140; the record keeping will then be rewarded by transaction fees solely.

In other words, bitcoin's inventor Nakamoto set a monetary policy based on artificial scarcity at bitcoin's inception that there would only ever be 21 million bitcoins in total. Their numbers are being released roughly every ten minutes and the rate at which they are generated would drop by half every four years until all were in circulation.

Wallets

A wallet stores the information necessary to transact bitcoins. While wallets are often described as a place to hold or store bitcoins, due to the nature of the system, bitcoins are inseparable from the blockchain transaction ledger. A better way to describe a wallet is something that "stores the digital credentials for your bitcoin holdings" and allows one to access (and spend) them. Bitcoin uses public-key cryptography, in which two cryptographic keys, one public and one private, are generated. At its most basic, a wallet is a collection of these keys.

There are several types of wallets. Software wallets connect to the network and allow spending bitcoins in addition to holding the credentials that prove ownership. Software wallets can be split further in two categories: full clients and lightweight clients.

- Full clients verify transactions directly on a local copy of the blockchain (over 134 GB as of October 2017), or a subset of the blockchain (around 2 GB). Because of its size and complexity, the entire blockchain is not suitable for all computing devices.

- Lightweight clients on the other hand consult a full client to send and receive transactions without requiring a local copy of the entire blockchain (see simplified payment verification – SPV). This makes lightweight clients much faster to set up and allows them to be used on low-power, low-bandwidth devices such as smartphones. When using a lightweight wallet however, the user must trust the server to a certain degree. When using a lightweight client, the server can not steal bitcoins, but it can report faulty values back to the user. With both types of software wallets, the users are responsible for keeping their private keys in a secure place.

Besides software wallets, Internet services called online wallets offer similar functionality but may be easier to use. In this case, credentials to access funds are stored with the online wallet provider rather than on the user's hardware. As a result, the user must have complete trust in the wallet provider. A malicious provider or a breach in server security may cause entrusted bitcoins to be stolen. An example of such security breach occurred with Mt. Gox in 2011.

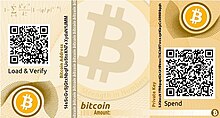

Physical wallets store the credentials necessary to spend bitcoins offline. Examples combine a novelty coin with these credentials printed on metal. Others are simply paper printouts. Another type of wallet called a hardware wallet keeps credentials offline while facilitating transactions.

Reference implementation

The first wallet program was released in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto as open-source code. Sometimes referred to as the "Satoshi client", this is also known as the reference client because it serves to define the bitcoin protocol and acts as a standard for other implementations. In version 0.5 the client moved from the wxWidgets user interface toolkit to Qt, and the whole bundle was referred to as Bitcoin-Qt. After the release of version 0.9, the software bundle was renamed Bitcoin Core to distinguish itself from the network. Today, other forks of Bitcoin Core exist such as Bitcoin XT, Bitcoin Classic, Bitcoin Unlimited, Parity Bitcoin, and BTC1.

Decentralization

Bitcoin creator Satoshi Nakamoto designed bitcoin not to need a central authority. Per sources such as the academic Mercatus Center, U.S. Treasury, Reuters, The Washington Post, The Daily Herald,The New Yorker, and others, bitcoin is decentralized.

Privacy

Bitcoin is pseudonymous, meaning that funds are not tied to real-world entities but rather bitcoin addresses. Owners of bitcoin addresses are not explicitly identified, but all transactions on the blockchain are public. In addition, transactions can be linked to individuals and companies through "idioms of use" (e.g., transactions that spend coins from multiple inputs indicate that the inputs may have a common owner) and corroborating public transaction data with known information on owners of certain addresses. Additionally, bitcoin exchanges, where bitcoins are traded for traditional currencies, may be required by law to collect personal information.

To heighten financial privacy, a new bitcoin address can be generated for each transaction. For example, hierarchical deterministic wallets generate pseudorandom "rolling addresses" for every transaction from a single seed, while only requiring a single passphrase to be remembered to recover all corresponding private keys. Additionally, "mixing" and CoinJoin services aggregate multiple users' coins and output them to fresh addresses to increase privacy. Researchers at Stanford University and Concordia University have also shown that bitcoin exchanges and other entities can prove assets, liabilities, and solvency without revealing their addresses using zero-knowledge proofs.

According to Dan Blystone, "Ultimately, bitcoin resembles cash as much as it does credit cards."

Fungibility

Wallets and similar software technically handle all bitcoins as equivalent, establishing the basic level of fungibility. Researchers have pointed out that the history of each bitcoin is registered and publicly available in the blockchain ledger, and that some users may refuse to accept bitcoins coming from controversial transactions, which would harm bitcoin's fungibility. Projects such as CryptoNote, Zerocoin, and Dark Wallet aim to address these privacy and fungibility issues.

Governance

Bitcoin was initially led by Satoshi Nakamoto. Nakamoto stepped back in 2010 and handed the network alert key to Gavin Andresen. Andresen stated he subsequently sought to decentralize control stating: "As soon as Satoshi stepped back and threw the project onto my shoulders, one of the first things I did was try to decentralize that. So, if I get hit by a bus, it would be clear that the project would go on." This left opportunity for controversy to develop over the future development path of bitcoin.

Scalability

The blocks in the blockchain are limited to one megabyte in size, which has created problems for bitcoin transaction processing, such as increasing transaction fees and delayed processing of transactions that cannot be fit into a block. On 24 August 2017 (at block 481,824), Segregated Witness went live, increasing maximum block capacity and making transaction IDs immutable. SegWit also allows the implementation of the Lightning Network, a second-layer proposal for scalability with instantaneous transactions.

Trailer Bitcoin

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.